When I stepped into the Jason control van at 0400 David informed me that I had just missed an albino octopus moseying across the screen. My hopes of the eight legged fellow returning were never realized. In the trail of the octopus were never-ending flat plains of the geologists’ least favorite rocks. Even void of dazzling biology and geology, the bottom of the ocean is still a rarely experienced scene so I was consumed by Channel Jason for 4 hours wrapped in my blanket like a crepe – which we had later that morning for breakfast.

After crepes, Roger explained to me the obstacles that this project has dashed in the past, which was more tiring than I had thought. The ACO project started over a decade ago with the first plans to set up this observatory using a copper telecommunications cable – the predecessor to the current fiber optics technology. The company that was going to donate this cable went bankrupt so could no longer give them the cable. It wasn’t until AT&T donated a fiber optic cable that the project regained momentum. The next obstacle appeared immediately when the programming prepared for communication with the observatory through a copper cable was not compatible with the code of AT&T’s cable. Someone cleverer than the cable tricked it into speaking ACO’s language and the project took another step forward. To prove that the cable system to Station Aloha worked, the project installed the predecessor to the observatory, the proof module. Mounted on the proof module was a hydrophone, which remained down there for over a year eavesdropping on whale songs and ships passing by. Roger let recordings of the whale sounds squeak and moo across the lab for a while. Because Jason wasn’t in the water, the pounding winch noises were absent and you could hear subtle clicks and whooshes from the sea. To replace the proof module came the first try at a installing an observatory with more instruments than just the one hydrophone. Faulty connectors prohibited this installation and bad weather cut the time for reinstallation of the hydrophone. The cable termination has been waiting patiently at Station Aloha since then for another try.

The news from Makaha, where troubleshooting abounds, is that there is nothing wrong with the cable itself between the termination frame and the AT&T station. This is good news – we don’t have to send someone swimming done to the bottom of the ocean to regenerate a regenerator or patch a fish bite in the cable. It does, however, mean that the problem lies elsewhere. We’ve yet to figure out where that elsewhere is. Working at Makaha alongside people from the ACO group is the original engineer of the fiber optic cable who flew into Honolulu to assist in tracking down the rascal errors.

Later in the day I pretended I was a geologist while the ones with degrees in Geology were describing their specimens. John said, “Let’s crack open those rinds,” and handed me a small metal object on a string. Thinking “crack open” meant something like The Mud Slinging Show of the previous day, I swung it around a couple of times trying to figure out how to I was going to exert force with this tiny weapon. “No, no, it’s a hand lens,” John said as he took it from me and opened it to reveal a magnifying glass. Crack open the scientific mysteries, he meant. They held rocks up close to their faces and crouched under the heating lamps with one eye squinting. “20% Olivine,” one says. “There are many vesicles in this one,” says another. If you can use these words in a scientifically accurate sentence, you are further than I. I know that vesicles are different than vessels and Olivine is shiny and green. My own observations – “This one looks like pâté,” – I kept to myself.

Yesterday was the day intended to be Jason’s launch of the signal test to Makaha. Over the past day, Jason’s umbilical cord had been reconfigured to extend out in front of him with a connector the same as those used throughout the observatory and J-box. Jason could then plug his bellybutton into the cable termination, connecting the lab on the KM up to the control van, down the winch wire, in one side of Medea and out the other, passing right through Jason and 100 km of fiber optic cable to Makaha. A regenerator in the lab would then produce an optical signal that anxious observers on land could receive. Like the whale songs, this signal would prove that communication is possible between land and sea. If the signal is not received, this is not necessarily an indication of the impossibility of communication – it just means we need to try something else. In the event of light seen at the end of the cable or not, the J-box would be retrieved on this dive for reconfiguration and redeployment.

Unfortunately, 0400 brought swell taller than four of my groggy selves standing on each other’s sleepy shoulders – conditions unsuitable for tossing Jason in, even with his remarkable swimming ability. When I woke for a second time at 0600, the swell was just as tall but now I could see it’s peaks and troughs fluctuate. The swell hung around for the rest of the day, as did the high 20-knot winds. Jason with his new protruding bellybutton rocked on the quarterdeck for the rest of the day.

Without Jason, there was little ACO work to be done. Instead, we prepared equipment for the next cruise. Already experts at switching batteries and cleaning o-rings, David and I flew through prepping a couple ADCP’s and their auxiliary battery packs. Of course, we couldn't have done it with the help of the Backstreet Boys and a little a cappella. These instruments will be attached to the WHOTS mooring in July. Though we had little to do on the ship to further the observatory installation, the folks at Makaha continued to tinker with their end, finding small errors here and there to correct.

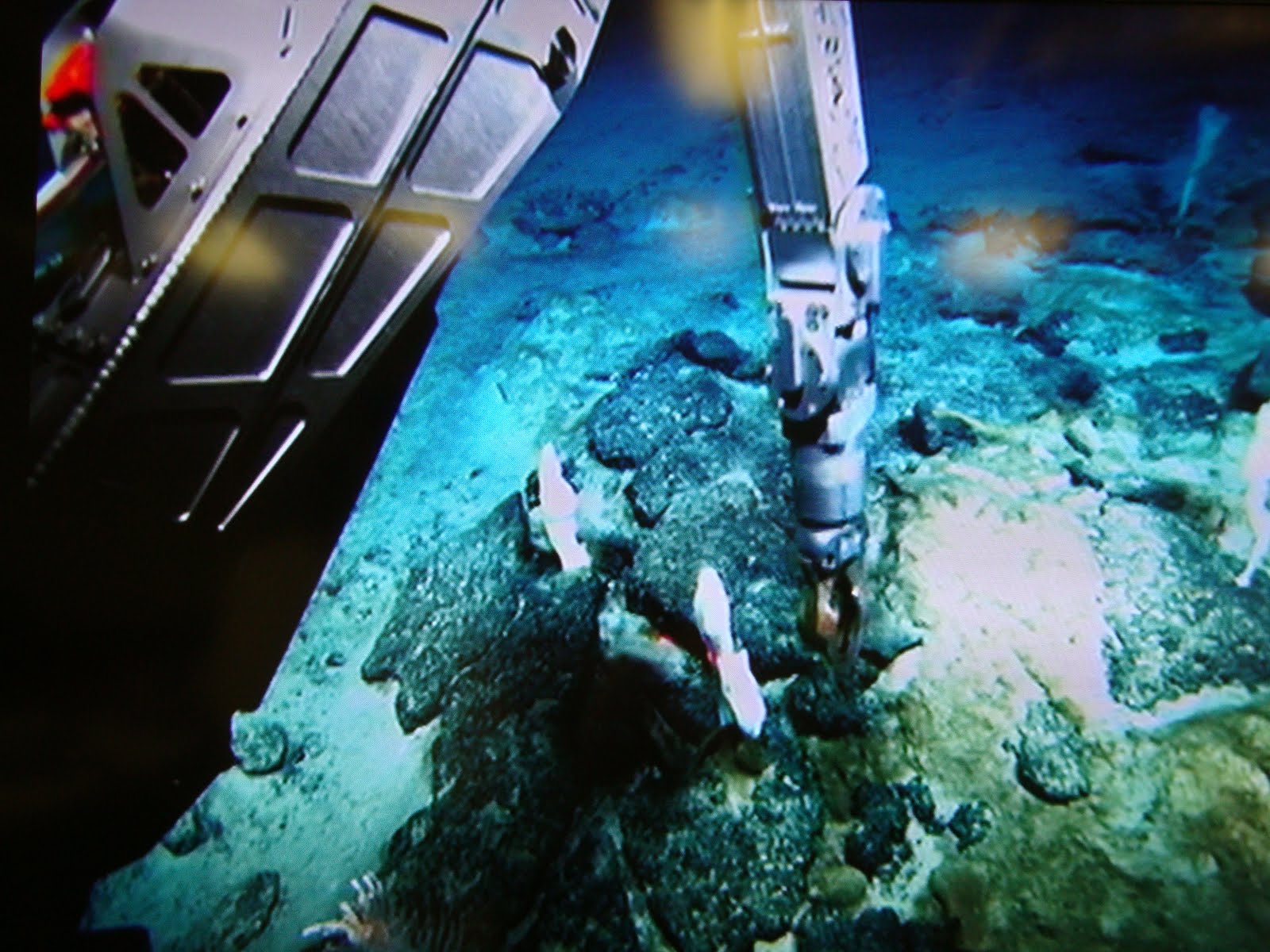

At 0400 this morning, the swells were quiet and the wind cut in half. Jason jumped in as I rubbed my eyes and drank my tea at the event logging station. The events were few on my 4-hour shift – limited to “Jason in water” and “Jason on bottom” with 3 hours of travel through the water column between. The rest of the dive will bring more information – and fish. In order to view a bit more biology at the sediment covered flat bottom, Jason brought with him fish carcasses. John hopes to find scavengers flocking to the smell -- possibly getting video footage of some for the first time. By 0800, when I was relieved, there was already a thin spattering of white in front of Jason – amphipods looking for their meal.